Wild to Table

A Hunter’s Ode to Tradition in the Natural State.

By Becca Bona

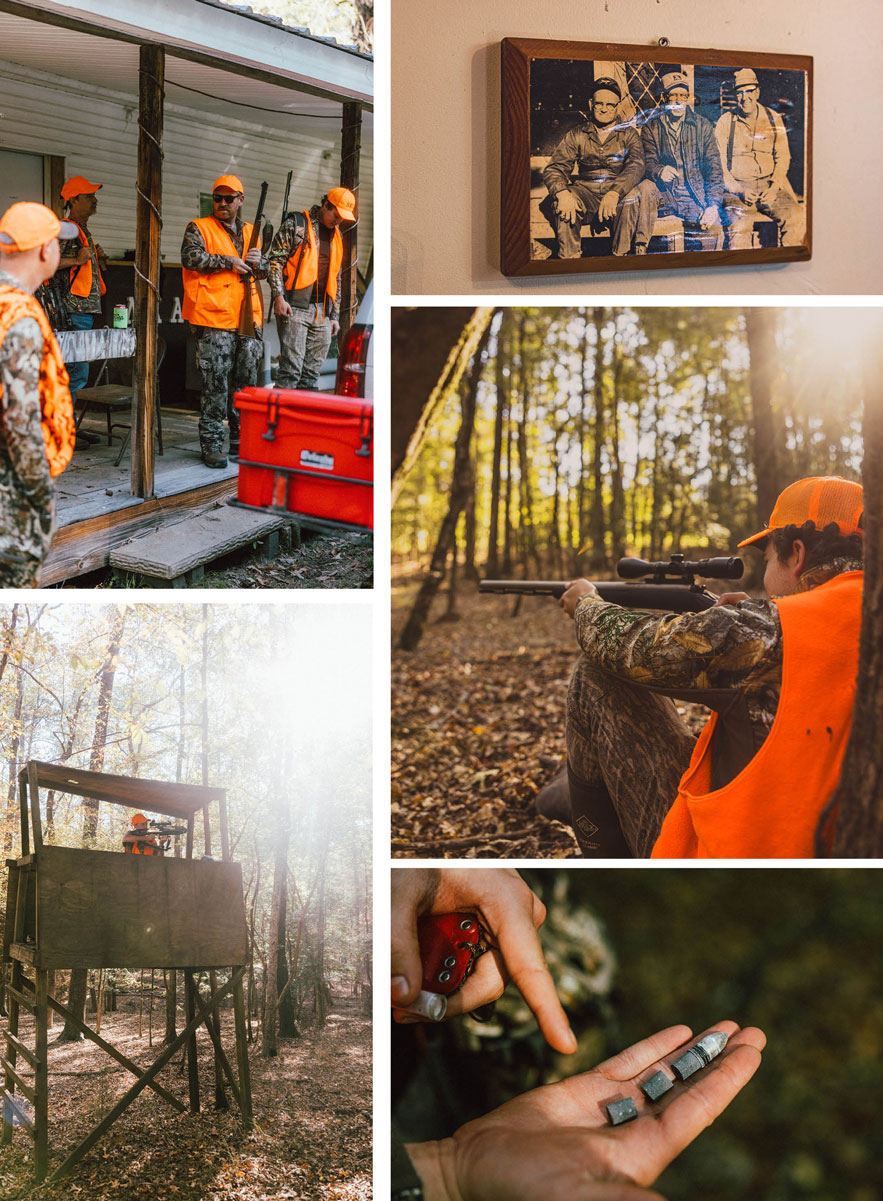

Hunting Photography By Novo Studio

Food Photography By Sara Reeves

One hunt, countless possibilities waiting in Mount Holly.

It was the early hours of a crisp, chilly morning in Mount Holly, Arkansas, when David McClellan and his son Will joined their friends Patrick Finley and John Martin on a hunting trip. These men don’t just hunt — they step into a long tradition that goes back centuries. Hunting is both primal and locked into nature’s natural order. For these friends, hunting defies the macho stereotypes; it’s a chance to reconnect with and respect the wild.

John Martin (left) followed by Patrick Finley (center) and Will McClellan (far right) head into the day, ready for the hunt.

A Hunter’s Story: David McClellan

The central focal point of this story is David McClellan, a beverage industry veteran who, according to his son Will, “knows a lot about a lot of things — especially wine.”

To get a good picture of hunting and why McClellan personally pursues it, it’s best to get a snapshot of its recent history. During and after the Great Depression, people hunted away almost all of the deer and bears that lived in Arkansas and Mississippi, where McClellan was born. “When my dad was a kid, he said that if you saw a deer track, he would call the newspaper, and they would come out and take a picture of it,” McClellan said.

Significant conservation efforts took place in Mississippi, Arkansas and regionally from the ’30s through the ’50s, reaching success in the ’70s in reintroducing deer into the area. Introducing rules and regulations also helps keep populations healthy, which McClellan and his crew are very careful to follow. “Identifying whether a deer is a doe or a buck is a big part of that. It affects what you can and can’t shoot. […] hunting is a big skill to master,” McClellan said.

McClellan credits his introduction to hunting to his father, who shared hunting stories with him early on. “My dad tells me that when he was a kid, they would anticipate squirrel season. There was so much excitement about the opening of squirrel season; the kids would stay up all night waiting on it because it was the only thing they had to hunt in the woods,” McClellan said.

A formative memory for McClellan includes spending time at a hunting camp with his father in the ’80s. At the time, the Mississippi camp had 600 members, mainly from the Gulf Coast. The hunt itself would be a full day, complete with lunch. “Generally, what people would do is they would get up early in the morning and they would still hunt. They would pick a tree, or if they built a deer stand, they would stay on it,” McClellan said. “Half of every deer you shot went to the hunting camp, and we had a staff there, and they cooked it up for lunch every day,” he said. “It was a true communal experience.”

McClellan moved to El Dorado, Arkansas, with his mom when he was 9 and took his love of nature with him. After he moved to Central Arkansas to go to college, he embarked on a path that would lead him to the food and beverage industry. He worked at Andre’s Hillcrest and then moved to Northwest to work at James at the Mill. Not long after, he switched to wholesale and has remained a wine and spirits wholesaler for 21 years.

Like his father before him, McClellan would ensure that his son could experience the tranquility of hunting. “My son started hunting with me when he was 7 or 8,” he said. “I think he shot his first deer at 8 with his grandfather.”

For McClellan, going down to Mount Holly is yet another communal experience, but it’s also his way of keeping a relationship with nature alive. In a world separated increasingly from our foodways by technology, Mount Holly is a must for McClellan, a food and wine connoisseur. He can hunt on land belonging to some friends, but he would find a way even if he didn’t have access. “We’re blessed in Arkansas with many public land and wildlife management areas. For instance, if you look at a state like Texas, they have almost no public land.”

Generations of skilled hunters will tell you it’s not about the gear or the size of the buck — it’s about the camaraderie, the tradition, and the chance to connect with the land.

A Seat At The Table

McClellan’s background in the food and beverage industry, plus his formative experiences at the Mississippi hunting camp, shape how he has built his hunting mythos. Namely, it’s open for sharing and doing what one ought to with the result of the hunt — eating. He wants everyone who’s willing to learn the skills needed to hunt properly to have a seat at the table.

“I think that interest in hunting has dwindled,” he said — that hunting camp of his youth only has 30 or 40 members now. “Not many young people are getting into it.”

Getting into hunting can come with a high price tag — from gear to licensure, plus the time it takes to learn in the first place. There’s also that pesky stereotype that hunting is gruesome, is only for the macho man, and is a premier way to escape your family. McClellan defied that mentality from the get-go and always opened his camp to family and friends.

His son Will backs up that way of thinking. “I think a lot of modern hunters go for trophies. I’ve never hunted for trophies or anything like that. We go to eat,” Will said.

Fellow beverage industry member John Martin credits McClellan for getting him into hunting. “As much as I hate to give David any credit — aside from one of my best friends — he is my hunting mentor. He was not the big buck guy but more of the process guy. Always talking about why we would put a stand here instead of over there, what’s the nature of the deer going to do, why we shouldn’t shoot those,” Martin explained. “One thing I wish we had more of … is people like David, who will teach people like me, I’m not his kid, I’m his buddy, how to go out there and hunt without being wasteful, as well as how to follow the rules,” Martin said.

The goal has always been to share the spoils, and McClellan and his team excel in culinary application. “John Martin and I are competitors but also close friends, and we’re both in the wine promotion business,” McClellan said. Once they finish their day of hunting, they enjoy prepping their table in the most no-frills, down-to-earth way possible. “We’re all sommeliers or chefs, and we cook delicious meals, open up hundreds of dollars of bottles of wine, and enjoy it out of red solo cups in the middle of nowhere, Arkansas,” Martin said.

They’re all chasing that connection with nature and the natural order of things. Hunting is yet another romantic process, like a traditional French recipe that dates back centuries or a rare bottle of Spanish wine.

“There’s something tranquil about just going out there. There are no expectations; everybody will be glad if you walk away with a cooler full of meat. But even if you go out there and have fun with friends and don’t get anything, nobody is upset. It’s nice to sit in the woods. I like it,” Will said.

Prepping the Table

McClellan is known by his family and friends as one who shares his spoils. From making his own sausage to playing with the flavors of venison, he’s always finding a way to add a new wine to the mix.

“We’ve learned a lot of things about cooking and eating venison in particular,” he said. “Used to, people would not clean them quickly. Venison had a reputation for being tough and gamey. And nowadays, we try to get it as cold as fast as possible and get it dressed as fast as possible,” he explained.

People thought that you had to cook venison to death because it was dangerous. But, as McClellan says, this isn’t the case: “And the truth is, there, deer meat doesn’t have any intramuscular parasites. It’s probably safer than chronic wasting disease. […] it’s cleaner, safer, obviously, all organic.”

Will McClellan said it best: “There’s something tranquil about just going out there. There are no expectations; everybody will be glad if you walk away with a cooler fool of meat. But even if you go out there and have fun with friends and don’t get anything, nobody is upset. It’s nice to sit in the woods. I like it."

McClellan enjoys mixing it up from the traditional stews and burgers. He likes for flavors to have their moments, to stand out and blend where necessary. From making his own traditional German hunter-style sausage to coming up with a new recipe for the latest game he’s brought in, McClellan loves tinkering with flavors. Enjoy the family and friend-approved Kung Pao Venison Recipe at the end of this piece.

And if you’re ready to consider hunting, take McClellan’s advice: Go with someone who knows the land. Hunting is not just about pointing a rifle; it’s about knowing when to move, how to quiet yourself in the woods and respecting the life you might take. For McClellan, that respect extends even into the kitchen, where he handles his venison with the same reverence as in the woods, chilling the meat quickly, butchering it with care and always seeking new ways to prepare it.

For these men, hunting isn’t just an activity; it’s a way to reconnect, learn from each other and share in the wisdom of the land. As long as people are willing to step into the woods, cook their venison over a shared fire, and teach the next generation about respect and resilience, the tradition will live on.

David McClellan’s Kung Pao Venison

Meat Marinade Sauce

• 2 Tbsp tamari or soy sauce

• 1 Tbsp cornstarch

• 1 Tbsp dry white wine

• 1 Tbsp vegetable oil

Slice 1 pound of deer meat (venison loin or backstrap) into ¼-inch-thick slices against the grain. Marinate in the sauce for one hour.

Stir-Fry Sauce Mix

• 2 Tbsp tamari or soy sauce

• 1 Tbsp rice vinegar

• 1 Tbsp organic cane sugar

• 1 tsp cornstarch*

• ¼ cup chicken stock

• 2 tsp sesame oil

*Note: Allow cornstarch to settle to the bottom. Use fingertips to mix the sauce.

To elevate the meal even further, David suggests pairing his venison Kung Pao dish with Origami Sake, Arkansas’s first and only sake brewery, based in Hot Springs.

Stir-Fry Ingredients

• 4 large garlic cloves, sliced

• ¼ cup minced fresh ginger

• 6 Fresno chiles, seeded, destemmed and cut into strips

• 1 bunch green onions, chopped

• 1 cup peanuts

Roast peanuts in a dry skillet and set aside.

Heat 1 cup grape oil until water sizzles in the pan. Stir-fry the deer steak slices for 1 minute, then set aside.

On high heat, pour out all but 2 Tbsp of grape oil from the pan. Stir-fry garlic, ginger, and Fresno chiles for 3-4 minutes until soft. Add the stir-fried deer steak and the stir-fry sauce mix. Cook for up to 1 minute, until the sauce reduces. Add the peanuts and green onions, stirring regularly.

Serving suggestion: Serve with steamed white rice and Origami Sake.

David McClellan is as skilled in the kitchen as he is in the field, turning his hunted venison into elevated dishes. His wife, son, family and friends swear by his gluten-free Kung Pao recipe.

David McClellan adding peanuts to his Kung Pao Venison.