Waterless Water Fowling

By Richard Ledbetter

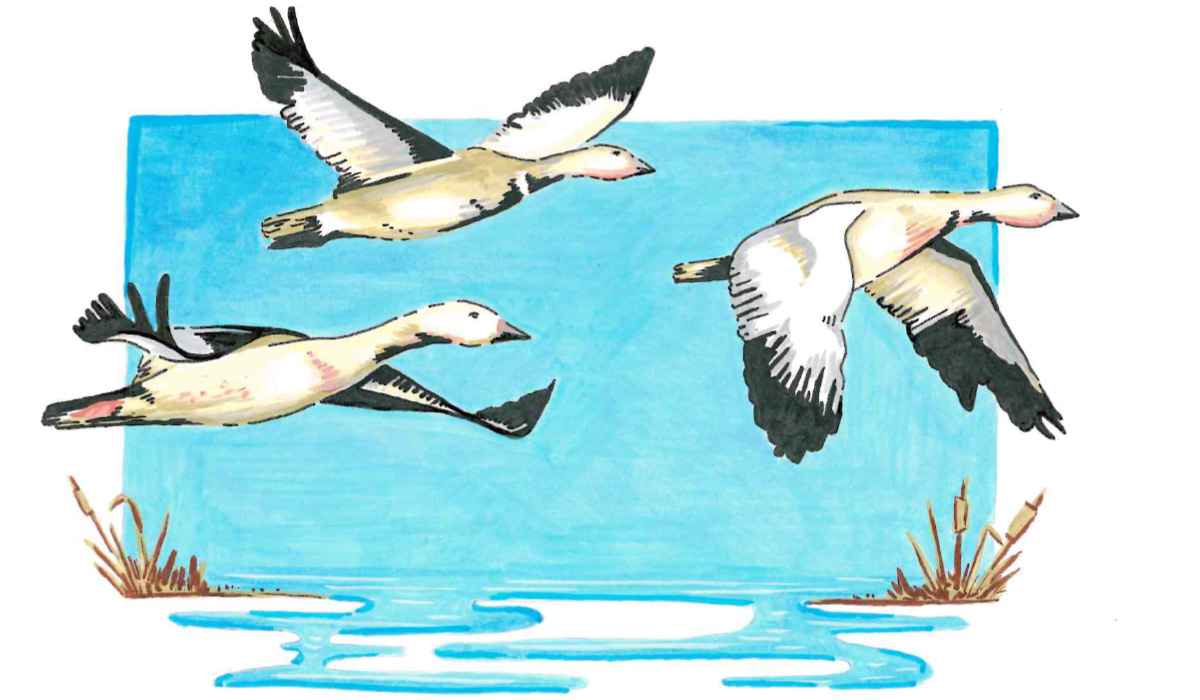

Illustration by @bumble_bri_artwork

D riving across the Grand Prairie this time of year, you’ll notice the great flocks of blue, snow, Ross’s and specklebelly geese filling skies and fields as they make their annual “grand passage” through the famous Delta flyway. While duck numbers have dwindled over recent years, many waterfowlers are switching from ducks to the more plentiful geese.

Being a longtime duck hunter, I’ve watched duck numbers rise and fall from season to season. Droughts in the Canadian pothole region affect nesting grounds where ducks hatch their young. Without proper water levels, hatches are reduced, leading to lower numbers during dry years.

Geese aren’t as impacted by drought. As a result, many waterfowlers have made the switch to goose hunting.

While blue, snow and Ross’s geese are abundant, they’re not considered as good to eat. “Specks,” on the other hand, are known as “the ribeye of the sky.” Most hunters agree, their large, flavorful breast filets are the tastiest of all waterfowl. Accordingly, the greater white-fronted goose (Ansar albifrons) has become the new bird of choice for avid hunters looking to bag a few birds.

Being new to the goose pursuit, I’m fortunate to know some of the finest goose hunters around. Dawson Miller, who has a lease east of Stuttgart, took me under his proverbial wing, inviting me along to learn the sport. Miller explained, “Because of their keen eyesight, concealment is critical hunting specks. Guide services set up temporary blinds in the overgrowth along ditches and levees lining farm fields. We hunt the same ground every day so we built a 24-foot box blind.”

Before daylight opening morning, six intrepid goose hunters, myself included, put out 150 specklebelly silhouettes to the north of the blind erected on a ditch-bank between two harvested corn fields. The day dawned clear and mild with a slight breeze. Early on, we called and knocked down five birds. Then, as the wind picked up and clouds thickened, flights slowed. Shooting slacked to a halt around 8. In the long interim between volleys, my companions enlightened me.

Of the 50,000 out-of-state hunters visiting Arkansas each season, many have converted to goose hunting. One of them is Jerod Petry, a Lafayette, Louisiana, dentist who regularly hunts with Miller. “I grew up hunting ducks in south Louisiana where we had lots of birds. But every year we had fewer ducks. Dawson told me how many specks you have up here so I checked it out. I saw 10,000 on my first hunt. I’ve been coming with friends at least six times a year ever since,” Miller said.

Petry elaborated, “Knowing when and what to call is key. There’s the two and three note yodel, the murmur, which is what they do on the ground, and the cluck,” he added, “is the ‘money’ call.”

Greg Jacobs, who has Old English Hunting Club, told me, “The sport began developing in this region about 15 years ago, only gaining popularity over the past decade. Ducks need flooded fields or flooded timber to land in. Goose hunters generally lure their quarry into dry fields where they glean rice, corn or soy beans left from harvesting annual crops. A flock can eat out a field in three days but they return to nearby standing water for day and night roost to protect them from predators. That keeps them in the area. They’ll move from dry field to dry field looking for fresh food, giving hunters the opportunity to bring them into shooting range.”

Petry added, “A dry field between two bodies of water is ideal.”

Jay Perry said with a grin, “Specks are the new greenhead!”

The goose-men further explained how hunting techniques vary from 150 to 600 goose silhouettes to spreads of white and speckled colored windsocks to smaller sets of full-body blocks, with combinations of everything in between. Accordingly, goose hunting requires more effort before daylight than most duck hunts do.

Each hunter is allowed two speckle-bellies per day during the 69-day season.

Following a long spell being overlooked by passing flights, Joe Salline voiced the idea, “Why don’t we split the decoy spread and move half of them to the corn field on the other side of us?” All agreed and the set was quickly redistributed. Sure enough, geese were lured to the new arrangement and six limits were filled in short order.

Petry said, “You have to be prepared to make a move when things aren’t working.” In regard to that morning’s harvest, he added, “We have a lot of young birds this year, which is good because they’re not as well-educated as specks who’ve passed this way before.”