Roadmaster Days

Eyewitness recalls AMF bike manufacturing in 1950s Little Rock.

By Stephen Koch | Photography by Kai Caddy

CRUISER: This AMF Roadmaster Nimble from the 1970s is one of the last styles of bike manufactured in Little Rock before the company moved.

Today, Arkansas is known as a haven for cycling, an oasis of trails and bike-friendly roads. But when AMF bicycle moved to the capital city in the mid-20th century because of a labor dispute in Cleveland, Ohio, the “Land of Opportunity” was better known for its acquiescent workforce.

In the mid-1950s, Beth Cripps, now 87, was part of that factory workforce. She was born in Murfreesboro, and grew up in Little Rock.

“I guess I was about 17, and I left school to work,” she said. “I didn’t go back for senior year — my family needed the money.”

She attended what’s now known as Central High School — and later did get her high school diploma.

Her then-boyfriend/future husband Jim Cripps had heard about the AMF company’s impending move to Little Rock, and he convinced Beth — then known as Beth Stuart — that this would be a good job for her.

“It was considered a sought-after job,” she said. “I started downtown. I was there on the very day they opened in East Little Rock, before they even moved to 65th Street.”

She soon got the impression that AMF brass from out-of-state regarded the workforce as rubes.

“They were coming to the South for the cheap labor, and there we were,” she said.

Teenage Cripps worked at AMF from 1955 to 1957.

For a period, the AMF Roadmaster bikes were a hot property, and the original location expanded a couple of times, Cripps recalls. But it soon moved to 4300 W. 65th St., with the company building a facility that could make 3,000 bikes a day. The new Southwest Little Rock factory was said to have held more than a mile of conveyor belts.

“At that time, there were a number of basic factories downtown, like Tuf Nut,” she said.

FOR THE LADIES: Another AMF Roadmaster from the 1970s, this one is a women's model.

For a period, the AMF Roadmaster bikes were a hot property, and the original location expanded a couple of times.

“When [AMF] moved to 65th Street, it was one of the first, if not the first one, out there.”

There was a ‘cafeteria’ – just vending machines, really – “but a lot of us brought our sack lunch, and we would buy chips or a Coke there.”

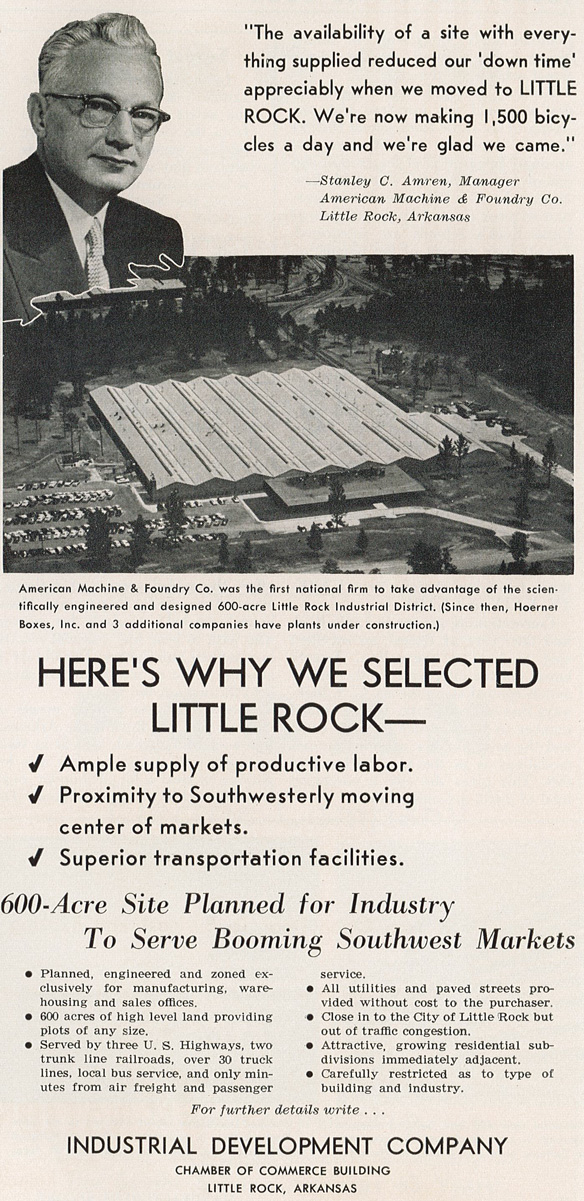

Said to be the first major ‘cycle unit’ ever located in the Southern United States, AMF President Morehead Patterson assured a reporter for a Chamber of Commerce-style city booster booklet that the new site “will in all respects be the most modern bicycle factory in the United States both in design and production methods.” Employment was expected to reach 1,000 people when the $1.25 million-dollar plant was in full operation – with 95% of the jobs going to locals. “We regard Little Rock as the ideal spot,” Patterson said.

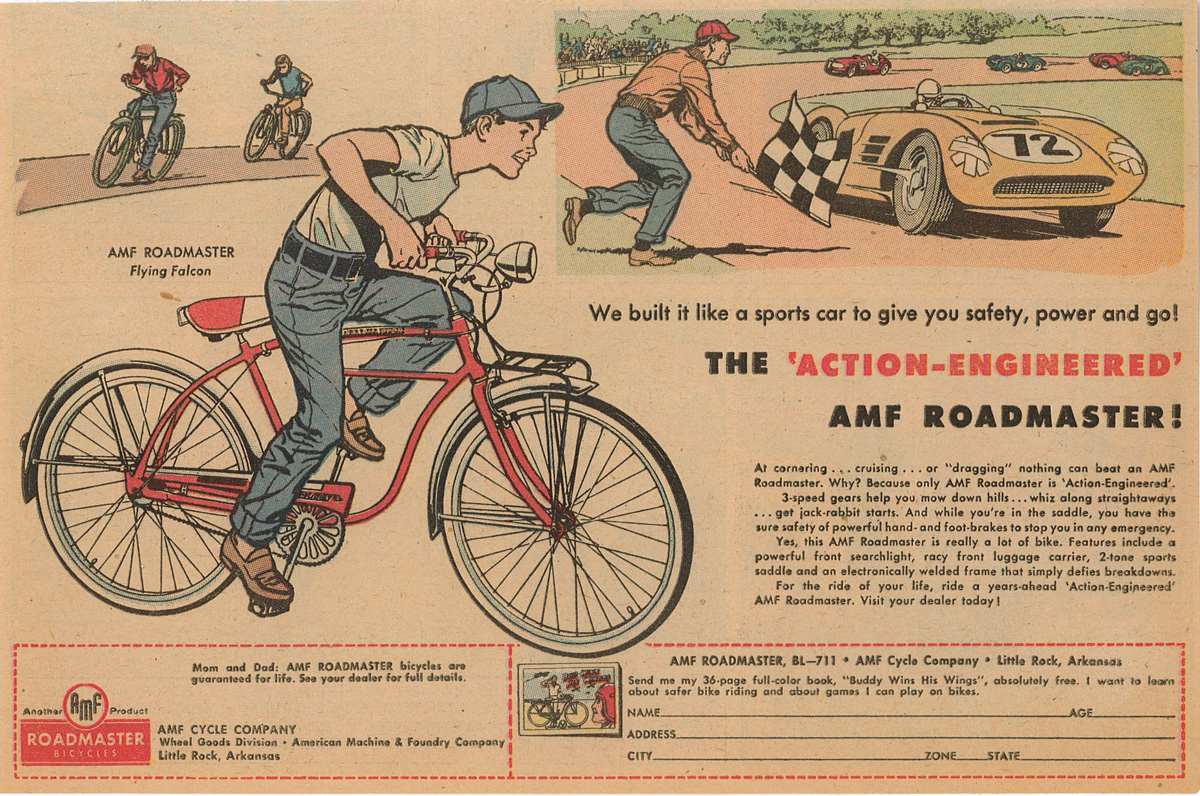

“Yes, this AMF Roadmaster is really a lot of bike,” an era print advertisement for the Little Rock-made 3-speed “Flying Falcon” touts, noting its “racy” front luggage carrier and standard front searchlight. “Cornering … cruising … or ‘dragging,’ nothing can beat an AMF Roadmaster. Why? Because only AMF Roadmaster is ‘Action-Engineered.’ ” Potential riders were encouraged to send off for a free 36-page comic book called “Buddy Wins His Wings” that included bike safety tips and bicycle games.

Some 65% of all parts for the bicycles were made on-site; the rest were shipped in. Cripps ended up in what was called the paint shop. Workers in the paint shop were mostly women, she said, but their supervisors were exclusively white men.

“Other departments had more men workers,” she noted.

She says the paint shop “was probably the easiest and the cleanest job” at the factory.

“But it was hot!”

“There was no air conditioning — but there wasn’t any air conditioning at home, either,” she said. “There was a conveyor belt; it made a long circle through my part that went through these baking ovens that dried the paint. Everything was hanging on chains.”

Cripps did decaling and silk screening on bike parts.

“I squeegeed on the decals, and there was a vat, or basin, to wash the silk screens in,” she said. “I only remember us doing two colors of bike — red and blue.”

Others in the paint shop actually did hand painting.

“One lady, with her hand and with a tiny brush, did pin-striping on all the fenders,” Cripps said. “She’d paint one side, then flip it over and paint the other side.”

The facility made bikes for other companies, too, she recalled, like Western Auto. Same bike, different decals.

ACTION-ENGINEERED!: An AMF Roadmaster Flying Falcon ad targeting children from the 1950s. (Courtesy Old State House Museum)

“One lady, with her hand and with a tiny brush, did pin-striping on all the fenders. She’d paint one side, then flip it over and paint the other side.”

Besides the relative cleanliness and ease of her department, another positive aspect of the paint shop was a lessened opportunity for dismemberment.

“I would say the paint shop was among the safest,” she said. “Other people were there working dangerous machines. People in other departments lost fingers and hands.”

Cripps recalled one chilling incident where “one guy, who we all loved, was overcome with fumes while working in a pit and died. He was about 19 years old. His job was to move the materials around, so most of us knew him. Many of us went to his funeral. [Working conditions] probably got better after I left.”

Despite its size and capacity, during her time there, the bike plant did not operate year-round — by design.

“We worked hard all year for Christmas delivery,” she said, “then we shut down for three months after, and had a Christmas party.”

Everyone went on unemployment until spring, she said.

“So we had a nice vacation around Christmas,” she said. “I’d never worked in a big factory before. I thought everybody was like that.”

Cripps got married to Jim during her time at AMF, and moved away.

“I lived in Indiana for six months til I got homesick and we came back to Arkansas,” she said.

But when she returned to Little Rock, she didn’t return to the bike factory.

Despite the rough working conditions at both Little Rock sites — which included actual death and dismemberment — Cripps remembers her time at the bike factory fondly.

“Actually, I loved it,” she said. “I was young enough and dumb enough that I didn’t know what hard work was; and that was hard work.”

However, Cripps never owned her own made-in-Little Rock Roadmaster bike.

“I had a bike in elementary school that I got for making straight As,” she said. “And I didn’t drive then. But I didn’t have a Roadmaster.”

There were factory employee reunions over the years, Cripps said, but she only went to one.

“I would guess there aren’t many of us left now,” she said.

AMF bikes did not remain a legacy manufacturing brand for the city of Little Rock. Seeking to expand again — and, ironically, having labor disputes again, but now in Little Rock, where it had moved to avoid them — the company subsequently moved its “wheeled goods” operations to a larger site in Olney, Ill. However, AMF Roadmaster bikes manufactured in Olney were said to be of such poor workmanship and substandard quality that some bike shops allegedly wouldn’t work on them. Eventually, the company shifted focus to bikes for younger children.

Today, Cleveland- and Little Rock-made Roadmaster bikes are prized by some collectors for their nostalgic caliber. And two Little Rock-manufactured models are even part of the permanent collection at the city’s Old State House Museum.

WHY LITTLE ROCK: This AMF ad from a 1956 Little Rock Chamber of Commerce publication “Industrial Little Rock” explains the company’s decision to move to Arkansas’s capitol city. (Courtesy Old State House Museum)

AMF: A Labored History

AMF is a retro conglomerate brand with plenty of history, but its often harsh capitalistic tendencies — including how its bicycle division even landed in Arkansas in the first place — can seem all too modern. First known as American Machine and Foundry, the company was doing hostile takeovers and brand acquisitions decades before it became commonplace. Besides bikes, U.S. consumers in the 1970s could find the AMF brand on sporting goods ranging from tennis rackets to boats.

AMF even once owned Harley-Davidson, buying the vaunted Milwaukee motorcycle company as it faced a hostile takeover from a different conglomerate. At first seen as Harley’s savior, AMF became widely despised among American motorcycle enthusiasts of the era for nearly destroying the H-D brand. AMF’s Harley reign saw removal of original management, quality issues, production bottlenecks — and, in a recurring AMF theme, disputes with labor. After more than a decade of turbulent tenure, Harley-Davidson was purchased back from the company in 1981.

Meanwhile, the bicycling world was also passing heavy-framed AMF bikes by — and well before the company divested itself from its bicycle division in the late 1990s. However, AMF Roadmaster bikes continue to be remembered fondly by a segment of mid-century nostalgists, while the company’s BMX bikes are mistily recalled by a subsequent generation.

Today, the last remaining AMF brand is associated with ten-pin bowling. In fact, due to its postwar embrace of automated pin-setting technology at bowling alleys across the U.S., AMF additionally is known by sports historians as the company that killed the once-widespread profession of bowling pin setter — additionally helping set the tone for the company’s scorched-earth corporate reputation.