Amid COVID-19, diminishing municipal revenue, high unemployment and an awakening to the negative impact unjust systems have had on our Black and brown neighbors, citizens across the country are demanding a change in the status quo. While the debate rages on how that change should happen, crafting and implementing mechanisms to deepen community value — physical, economic, social, political, legal, technological, environmental and cultural — remains a primary and invaluable role for a municipal government.

Calibrating governance toward innovation means intentionally looking at how various city departments interrelate, work together and function within the larger community ecosystem. Consistently reviewing the codes and ordinances that dictate that work should be a high priority for those communities that want to remain competitive in a global economy, and focusing on advancing the overall experience desired within a community should drive those reviews.

Crafting a community master plan provides a dynamic long-term document that should connect the various systems at play within a community; however, most of these plans spend the bulk of their pages dedicated to just the physical realm — development, land use, infrastructure — and provide little guidance in strengthening the more comprehensive realm of experience design.

An Experience Design approach offers an interdisciplinary practice that coordinates the “hardware” (development, land use, infrastructure) and the “software” (economy, brand, governance, activation), turning a standard planning exercise into a placemaking initiative. The municipal and organizational systems of community development, however, are often at odds with an Experience Design approach.

Most Arkansas cities utilize what is called Euclidean zoning, which is characterized by the segregation of land uses into specified geographic districts and defined limitation on development activity within each type of district based on that use. While advantages to Euclidean zoning include relative effectiveness, ease of implementation, long-established legal precedent and familiarity, this zoning approach has also been shown to exacerbate unsustainable suburban sprawl, urban core decay, racial and socioeconomic segregation, and an overall reduced quality of life. In addition, traditional Euclidean zoning ordinance doesn’t address building placement, mass and scale of buildings, especially in relationship to surrounding buildings.

A form-based code, which has been adopted in several communities across Arkansas, was created as a means of tackling the issues of mass and scale by regulating land development using physical form, placement, size and bulk of buildings as a legal design regulation. By outlining the desirable physical outcome, these codes go a long way in addressing the size of blocks and the physical relationships within the built environment. While intentional design with contextual relevance is more nuanced than traditional Euclidean zoning, the limitations of form-based code within an Experience Design approach is it focuses almost entirely on the physical realm.

Experience Design strategically merges use and form with the goal of producing an overall desired experience, thus creating metrics of growth based on performance and not just a resulting development product or based on isolated uses. It is important to note that this approach interrupts the one-size-fits-all zoning categories prevalent in Euclidean zoning and is more akin to form-based code for its block, street and building application.

Getting started

It is first necessary to establish a geographic boundary in which the Experience Design effort will be focused and for which a set of goal-oriented criteria called guiding principles will act as a decision filter for the characteristics of design, form and function. These principles are developed in partnership with the community and should align current neighborhood context and future development ambitions, advance a diverse cultural and arts environment, forward a robust economic ecosystem, create strong civic organizational support, deepen community affinity and celebrate the community’s unique personality.

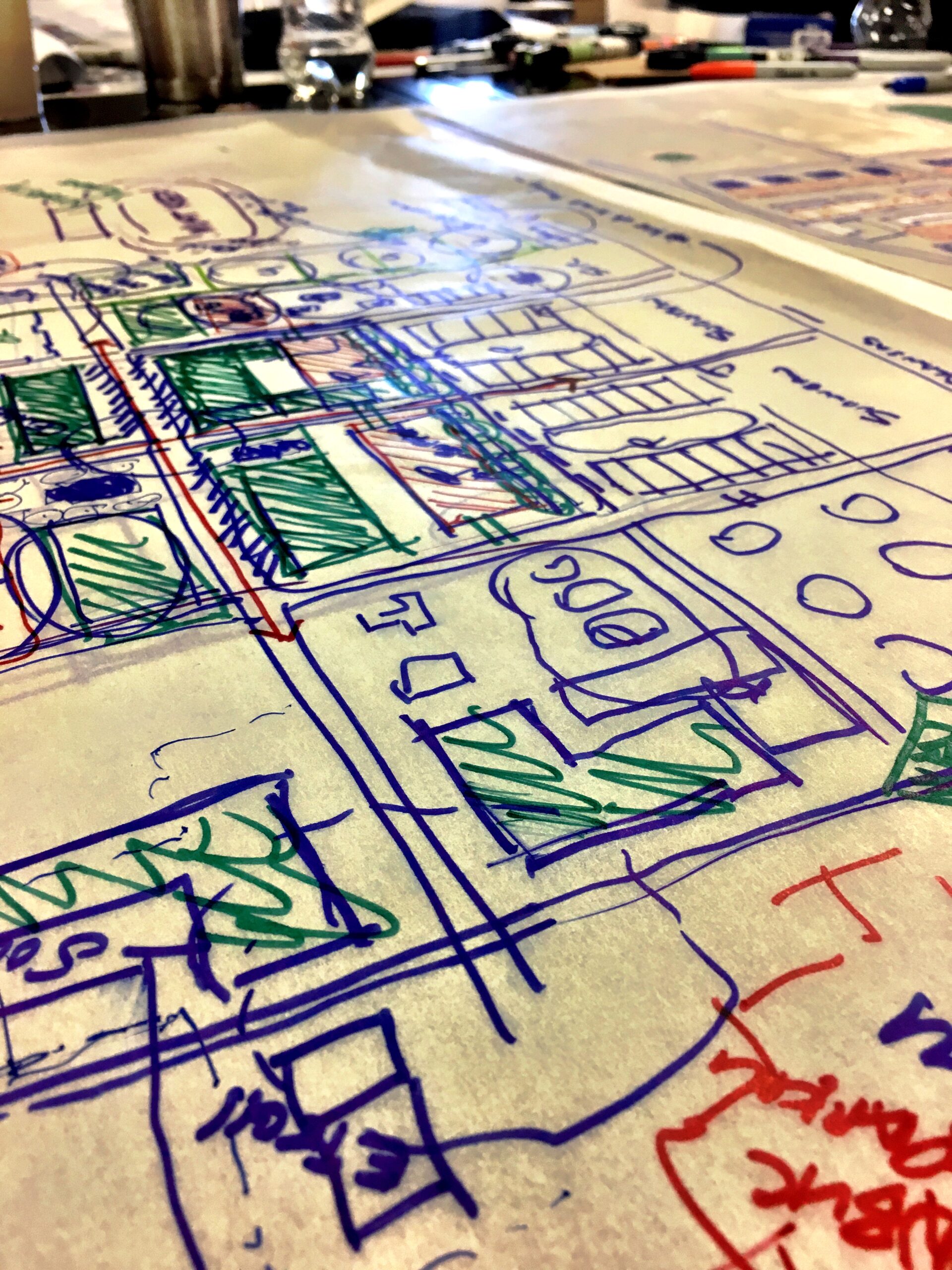

Recognizing that Experience Design needs a nuanced and detailed plan, it is vital to take a deep dive into the geographical area to tease out and map unique centers of desired activity no larger than six blocks. Each of these areas should build on distinct assets that lend to an inclusive neighborhood identity. It then becomes easier to do a quick audit to identify issues that detract from the desired experience within each district and to identify the needed codes, ordinances, municipal investments, economic development strategies and activation plans that forward both the overall area and the unique neighborhood plan.

Elements to consider in the audit include streetscapes and sidewalks, street design, building typologies and desired development patterns, trails and connectivity, infrastructure and utilities — as well as locations of public spaces and catalytic projects that drive immediate investment. Elements to consider for strategic placement are wayfinding and signage, new restaurants and retail concepts, food trucks, public art, stages and performance areas and branded street furniture.

Crafting the props for the experience

Curating the details of place by breathing life into the public realm and aligning adjacent private market elements help fuel the experience-based economy necessary to realize the full value of the experience design approach.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly impacted the ability to gather, now is the time to address the institutional elements that foster an integrated and positive community experience. Alignment between new development and a clear community vision, efficient collaboration between municipal departments and innovative frameworks in which they function, focused public investment strategies that forward both an economy and broaden opportunity and constant citizen feedback loops are the pillars of a robust community Experience Design initiative. This work will pay dividends in a post-COVID world.

Daniel Hintz is CEO of Velocity Group, an national urban design firm, and Blockline, LLC, a property development company focused on urban infill projects.