The world wrestles with the challenges of a global pandemic without the opportunity to travel. Within their own cities, people have had no choice but to pay more attention to their immediate surroundings. City governments are hearing less about potholes and more about parks; less about parking lots and more about places to walk. Quality of life has been a growing issue for cities over the past decade, but the pandemic has focused attention on the issue.

Increasingly, people want to live in neighborhoods that support community, safety, diversity, health and identity. These characteristics signal a return to traditional neighborhood design and an appreciation for urbanism. Cities recognize the negative impact from low-density, single-use zoning, which segregates daily life into silos of housing, employment, recreation and basic services. These development patterns foster pockets of intense growth and swathes of neglect. Successful cities embrace the power of density, mixed uses and walkability. They celebrate and amplify the unique character of the place and its people.

Today, cities recognize the importance of urbanism and are struggling more than ever to find effective ways to spur development. The reality is that to be effective, big ideas often require significant changes to the status quo. Change requires an increased level of risk and investment, which is something that many state and municipal entities avoid at all costs. Sadly, the few efforts that do pass muster often become watered down and rendered ineffective by the very bureaucratic process that is trying to encourage them. In recent years, however, several grassroots movements developed their own ways to navigate this quagmire and drive progress by quickly testing proposals at full scale and in real time. Enter tactical urbanism.

Tactical urbanism is not a new concept. It focuses on temporary interventions often completed over a weekend. These interventions often lead to positive and permanent change. Over the past decade, tactical urbanism has grown into an international movement inspiring projects all over the globe, including several across Arkansas. One of the state’s notable examples is the annual PopUp in the Rock program, which started in 2012.

PopUp in the Rock began when Create Little Rock, the young professional wing of the Greater Little Rock Chamber of Commerce, partnered with the design advocacy and public outreach group studioMAIN. Together the organizations were the perfect team to bring tactical urbanism to Central Arkansas. Create Little Rock was able to utilize its business and chamber contacts to find participating businesses and vendors. The nonprofit studioMAIN provided architects, landscape architects and urbanists to develop a collaborative process between design professionals, the general public and city government.

Their inaugural project, PopUp Main Street, settled on South Main Street in the area now commonly referred to as SoMa. At the time, it was an underutilized area with good urban bones, even if it was on the “wrong” side of the interstate and several of the storefronts were empty. The perception of the community was beginning to transition from dangerous neighborhood to up-and-coming hot spot. With brand-new businesses like The Root Cafe, the recently constructed Bernice Gardens and Pavilion and the soon-to-be South on Main, the only thing holding SoMa back was the road dividing it.

While interviewing community members, the PopUp team heard countless near-miss tales involving pedestrians, cyclists, dog-walkers, mothers with strollers, even local bakers pushing bread carts across the road. At that time, South Main Street had two traffic lanes in each direction, with low overall traffic volume. This led to an average speed of 37 miles per hour in an area with a posted speed limit of 25 miles per hour. Moving at this speed, drivers ignored crosswalks and didn’t have enough time to notice local businesses as they sped by. This was a huge problem, and a local group had even proposed to put Main Street on a road diet, reducing the area allocated for cars and increasing areas allocated for people.

City staff agreed that it was a good idea, but a road diet hadn’t been done in Little Rock before and wasn’t considered immediately feasible. A report was put together, bound and placed on a shelf at the planning department. That plan may well have collected dust and died on that shelf, until their road diet became the linchpin of PopUp Main Street.

The PopUp team knew immediately that if it wanted the project to catalyze permanent change, it needed everyone to buy in: the city, the community, the chamber, existing businesses, everyone.

To develop support, PopUp Main Street held bi-weekly open house project meetings. These included design charettes for city officials and downtown organizations, local businesses and neighborhood associations and the public at large. The largest of these meetings attracted over 100 participants. The needs and desires of the community quickly became clear: slow down the cars, fill up the empty storefronts and create activity along the sidewalk.

The final PopUp Main Street plan included reducing the road from four lanes to two lanes, adding a planted median with trees and a dedicated bike lane in each direction. The plan also created streetside cafe seating from reclaimed parallel parking spots, a Goodwill store, bike parking, Etsy vendor stalls, murals by local artists, a food truck park and a dog park. This major transformation only cost a few hundred dollars using tools like duct tape, wooden pallets, hay bales and the support of a community filled with excited volunteers.

The effect upon the South Main community was apparent immediately. PopUp in the Rock gave the community members an opportunity to reclaim control over the neighborhood they loved and demystified the planning process. It was safe to cross the streets. Folks who had never visited South Main came by the hundreds. Local businesses had banner days, and traffic speeds slowed by nearly 14 miles per hour. In fact, PopUp in the Rock had so much success that the city of Little Rock got a $750,000 grant to have Main Street permanently restriped from four lanes down to two with a center turn lane, and dedicated bike lanes in both directions.

The PopUp Main Street event became a real-time proof of concept. It allowed both the city and the community to test new ideas without the risk of costly backtracking and finger-pointing. A temporary intervention of duct tape and hay bales led to permanent change. SoMa has continued its evolution from empty storefronts and speeding cars to a lively neighborhood with restaurants, shops, parks and public art.

The PopUp in the Rock program continues to this day as an annual community revitalization effort. The program showcases the potential of cities, block by block, and demonstrates that temporary interventions can deliver permanent change. In subsequent years, PopUp in the Rock has supported multiple communities around Central Arkansas.

In 2013, PopUp 7th Street infilled empty storefronts and created pedestrian infrastructure for a busy intersection shared by local eateries, the central fire station and EMS services. The following year, PopUp Park Hill tackled a town center split by a state highway with an event that had over 5,000 attendees.

In 2015, PopUp focused on the historic Ninth Street neighborhood in Little Rock. The event attempted to recreate the rich fabric of the historically African American area in partnership with the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center. In 2016, the PopUp event was held at the River Cities Travel Center to highlight the potential of transit-centered development. PopUp in the Rock partnered with Rock Region Metro to facilitate the three-day event, which included live music, health clinic, food trucks and small lending library for the travel center patrons.

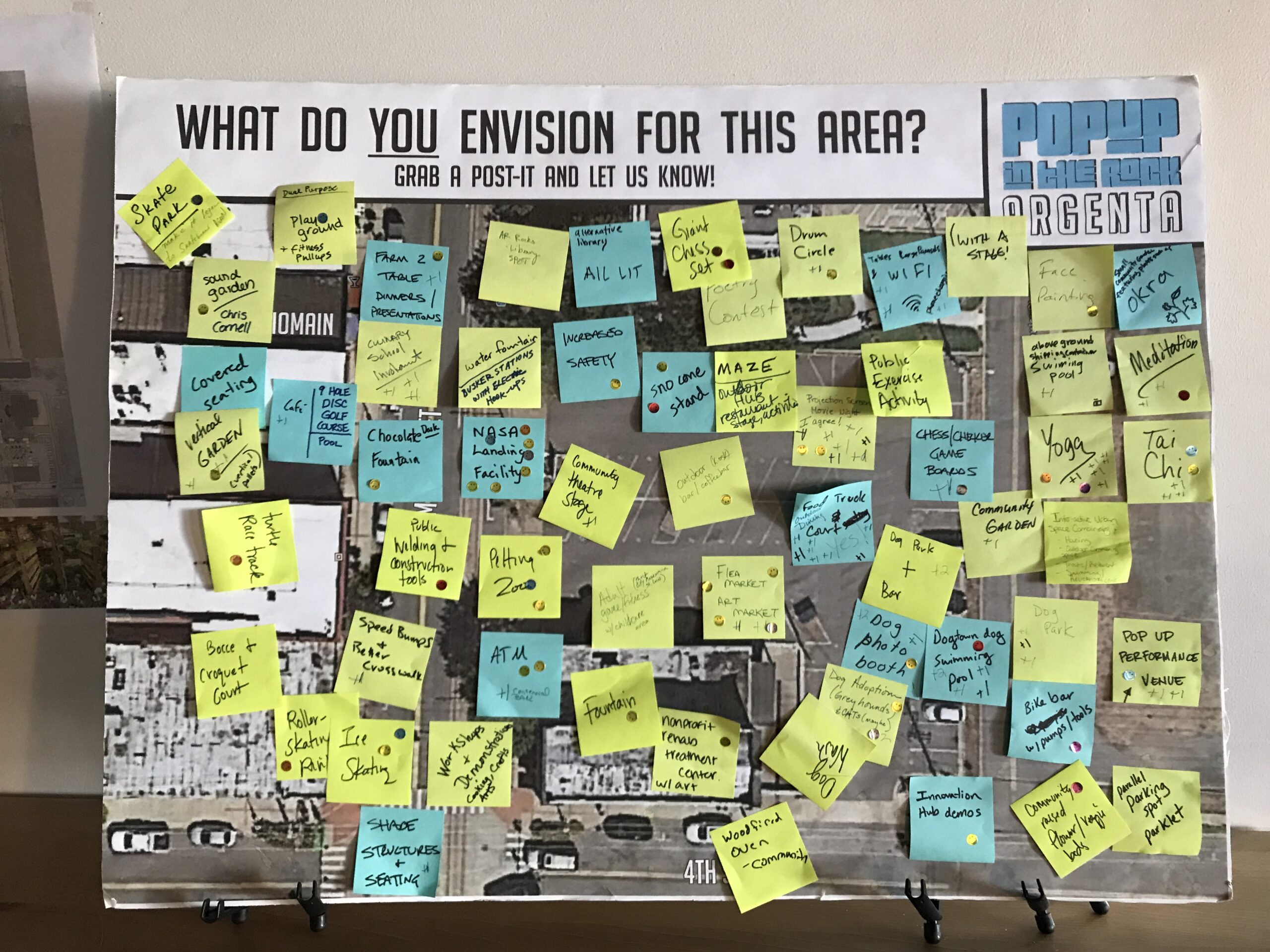

PopUp Argenta created a vibrant outdoor market and stage along North Little Rock’s Main Street in 2017. The project acted as a test vehicle for the now completed Argenta Plaza. In 2018, PopUp Stifft Station revitalized a busy intersection between two neighborhoods, with new pedestrian crossings, infilled storefront and public art. Within six months of the PopUp event, adjacent building occupancy went from 40% to completely full, with multiple new businesses. PopUp Southwest brought the program to the Geyer Springs area in 2019 and highlighted the great local minority-owned businesses. Recently, PopUp in the Rock began developing a tactical urbanism neighborhood intervention kit to provide solutions for common problems that communities can apply for through a simple city permit process.

The PopUp in the Rock program has been proof positive that tactical urbanism works and that short-term action can lead to long-term change. By temporarily transforming just a few blocks into a thriving, complete locale, these events show that community-driven design can make our cities better, one weekend at a time.

Chris East is a principal architect with Cromwell Architects Engineers and president of studioMAIN. James Meyer is an architect at Taggart Architects and a co-founder of studioMAIN.

Weekend warriors: The power of tactical urbanism.